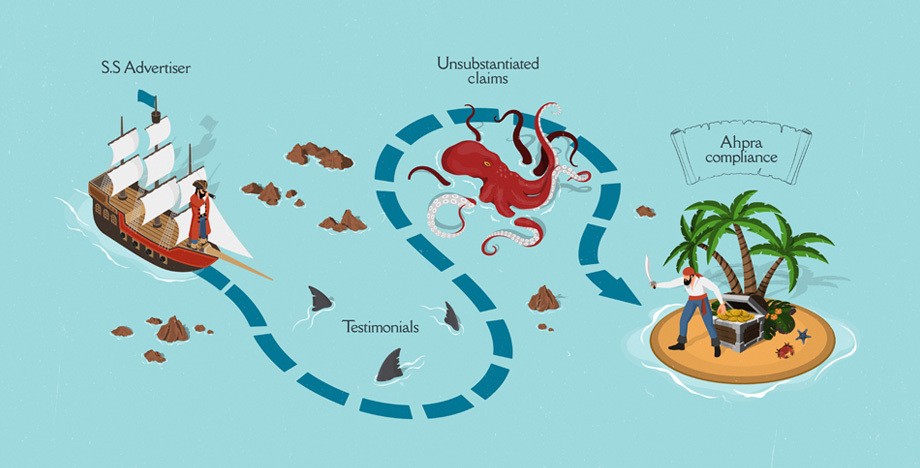

When I think about the word ‘guidelines’, I’m instantly taken back to the film Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. It was upon the deck of the Black Pearl that Elizabeth Swann, daughter of the Governor of Port Royal, found herself negotiating with pirates. Refusing to take Miss Swann back to shore, Captain Barbossa famously stated that ‘the code is more what you’d call guidelines than actual rules.’

Unlike pirate code, however, the Australian Health Practitioner Agency (Ahpra) guidelines are actual rules that must be met under National Law. Prosecution for non-compliance could result in a hefty fine.

All registered healthcare practitioners are on notice since Ahpra announced a nationwide audit of advertising compliance late last year. Marketers and agencies involved in advertising healthcare services should also sit up and take note.

Alongside the various national health practitioner boards (the National Boards), Ahpra oversees the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme and Health Practitioner Regulation National Law.

Ahpra and the National Boards regulate Australia’s health practitioners to keep the public safe from harm.

They set various standards that health practitioners must meet to maintain their registration and right to practise.

Anyone registered with one of the following National Boards is legally bound by the advertising guidelines:

Henceforth, the term ‘Ahpra’ also implies a reference to the National Boards.

In a nutshell, the guidelines explain what you can and can’t do when it comes to healthcare advertising.

Advertising health services and treatments is an essential element of sharing important information with the public. It also has the potential to wield great influence on consumer decision-making – for better or for worse.

Ahpra’s intent, rightly so, is for advertisers to provide accurate information supported by high-quality evidence, without misleading the consumer. Like most healthcare practitioners and marketers, the regulator wants the public to be able to make well-informed choices about their healthcare.

To this end, Ahpra has compiled the must-read resource Guidelines for advertising a regulated health service (recently updated in December 2020).

Be warned that it is the registered health practitioner who is held ultimately accountable, even if the advertising content was developed on their behalf by a third-party.

As a marketing and communications agency specialising in healthcare and pharmaceutical advertising, Ahpra’s advertising guidelines is one of our ‘bibles’. Others include the Medicine Australia Code of Conduct and the Therapeutic Goods Advertising Code.

Make sure you understand Ahpra’s definition of ‘advertising’ – you might be surprised at what is included.

In addition to a structure overhaul, Ahpra has provided further clarification in several areas.

Important information is more prominently located in the new document. Easy-to-follow flowcharts have also been added. These help advertisers decide whether acceptable evidence is required or if an online review counts as a testimonial.

I explore some of the key areas covered in the guidelines below. Alternatively, feel free to get in touch for a more comprehensive discussion about your healthcare advertising and the Ahpra guidelines.

Advertising claims about the effectiveness of a regulated health service need to be supported by credible evidence. The guidelines contain new content describing the type of evidence that is acceptable.

This should feel familiar if you have a scientific or academic background. Ahpra directs advertisers to use robust evidence such as systematic studies in peer-reviewed publications.

Acceptable evidence ranks highly against these six factors:

Those that fail to meet the acceptable standard include:

Ahpra has provided more detail around the use of titles and claims about registration, competence and qualifications.

It remains illegal to misuse a protected title. Unsurprisingly, you can’t call yourself a dentist if you aren’t registered as one in Australia.

Ahpra recognises that the word ‘specialist’ (and variations thereof such as ‘specialises in’, ‘specialty’ and ‘specialised’) can mislead consumers and must be used carefully.

For example, saying ‘Dr Lopez (Chiropractor) is a specialist in paediatric chiropractic care,’ is easily interpreted as Dr Lopez holding specialist registration in paediatric chiropractic care.

This isn’t the case as chiropractors currently do not have agreed and accredited pathways for specialisation. In fact, it’s only medical professionals, dentists and podiatrists who have recognised specialist registration categories.

Ahpra recommends using language like ‘substantial experience’ or ‘working primarily in’ to avoid any confusion.

Providing details about a practitioner’s education, training and experience can assist consumers in making an informed decision.

It’s also perfectly acceptable to advertise postgraduate qualifications, memberships and specific work experience on the proviso you don’t infer that you have more qualifications, skill or experience than is the case.

While the title of ‘Doctor’ isn’t protected, Ahpra emphasises that most people think of doctors as medical practitioners. If you use the title ‘Dr’ but aren’t registered with the Medical Board of Australia, make sure your profession is immediately clear.

The guidelines use this example: Dr Lee (Osteopath).

The prevalent use of testimonials in healthcare advertising is a particularly contentious issue.

Many regulated health services use testimonials in their advertising in a way that does not comply with Ahpra’s guidelines.

Specifically, testimonials of a clinical nature are not acceptable on any platform under your control. This includes purported testimonials and (although it seems obvious) fake testimonials.

Yet, that’s not to say all testimonials are out. The guidelines permit sharing patient experiences of the non-clinical aspects of a service (e.g. friendly reception staff).

Online patient reviews are allowed on websites, forums and social media platforms outside your control. However, you shouldn’t reference these in your advertising if they mention any clinical aspects.

Like testimonials, this is another area that generates a lot of controversy – can you or can’t you? Again, it depends.

Any offer of a gift, discount or inducement must be accompanied by the terms and conditions in clear, easy-to-understand language that is not misleading.

Ahpra specifically uses the word ‘free’ as an example. Public expectation of a ‘free offer’ is that it is absolutely free and not recovered from a third party (e.g. Medicare) or by raising your fees elsewhere.

You’ll also want to take great care that your offer does not encourage the indiscriminate or unnecessary use of a regulated health service. This is particularly the case if the value of your offer distorts the consumer’s perception of the cost and risk of the treatment.

Here is Ahpra’s example of a potential breach:

‘Each time you attend for cosmetic injections at our practice you go into the draw to win a luxury car. The more times you attend the more entries you get and the more chances you have to win!’

When it comes to healthcare advertising, keep your patients’ best interests top of mind to increase engagement and reduce the risk of non-compliance with Ahpra’s guidelines.

With so much at stake, finding the right balance between Ahpra compliance and effective healthcare advertising can be tricky.

But it needn’t be. If you want to make sure your healthcare advertising is shipshape and ready to sail, give us a hoy!

Download Ahpra’s Guidelines for advertising a regulated health service here.

Disclaimer: Although our writers all have life science degrees (including medicine and veterinary science) and apply Ahpra’s advertising guidelines on a daily basis, we are not lawyers and cannot provide specific legal advice regarding compliance with advertising under the National Law. Note too that Ahpra and the National Boards cannot advise whether specific instances of advertising are legally compliant – you’ll need to consult a legal adviser or indemnity insurer instead.