When I was a kid of about 7 or 8 years of age, I became borderline-obsessed with the movie Chariots of Fire.

If you know Chariots of Fire, I’ll give you a minute to roll your eyes, because it probably seems like a ridiculously pretentious choice of entertainment for a young lad. It’s a fair cop.

What can I say? I guess I was taken in by all the running, perhaps thinking I would one day become an Olympic champion (spoiler alert: I didn’t quite make it).

But before long – or so I like to tell myself – I began to understand the real themes of Chariots of Fire. Let’s just say it didn’t win four Academy Awards for being a film about some blokes jogging along a beach.

Chariots of Fire is the mostly true story of two British men who competed at the 1924 Olympics. One, Eric Liddell, is a devout Christian who would later become a missionary in China. He sensationally refuses to run an Olympic heat on a Sunday – on account of it being the Sabbath – and therefore forfeits his favourite event, the 100 metres.

Eric Liddell literally believes that he runs for God. More figuratively speaking, he tells his supporters that faith will give them the power ‘to see the race to its end’ (one of many lines in the film that makes me well up, despite my avowed atheism – honestly, I implore you to watch this scene if you haven’t seen it before).

The other protagonist, Harold Abrahams, is a Jewish man who is driven by resentment at being cast as an outsider by the British society of the time – and particularly by the anti-Semitism he encounters. As he later explained in a BBC interview: ‘I attached so much importance to my athletics as a means of demonstrating that I wasn’t inferior’. So where Liddell’s motivation was faith-based, Abrahams’ was a highly personal animus.

At the risk of trivialising such a profound theme, I think it has a parallel in marketing.

Demographically speaking, Eric Liddell and Harold Abrahams had a lot in common. Both were university-educated British men, of a similar age, who won Olympic gold medals (OK, admittedly that last bit isn’t exactly a demographic category).

But despite their superficial similarities, these two men were vastly different people in terms of their beliefs and motivations.

This is why generalisations, especially demographic ones, can be risky. Not to say that demographics are useless – they may be handy heuristics at times – but they do need to be treated with caution.

I’ll give you an example.

If you follow the industry media or Twitter trends or just about any other form of contemporary marketing discourse, you’ll know that Gen Z is the generation du jour in marketing.

If you’ve been in the industry more than a couple of years, you’ll also remember that this honour used to belong to millennials. Those days are long gone (despite being practically yesterday), because Gen Z have usurped millennials’ place in the marketing industry’s consciousness just as surely as millennials once did to the generation before them.

(Spot quiz: what was the generation before millennials? Aha, trick question! We don’t care what it was – all you need to know is that it’s prehistoric in marketing terms.)

You see, just like their millennial predecessors, people in Gen Z are completely different from all who have gone before. They might as well be from another planet, such is the awed fascination with which their habits are observed by marketers.

Apparently, members of Gen Z are almost uniformly ‘sceptical’, ‘pragmatic’, ‘shrewd’, ‘authentic’, and ‘driven by passion and cause’. Even more specifically, their attention span is exactly eight seconds.

Now, I don’t claim to be an expert on youth culture (stop laughing), but I’ve studied and practised psychiatry so I have some understanding of human psychology. And unless the human brain has taken a sudden evolutionary right-turn in the last few years – after several thousand years of not doing so – it seems likely that people who happened to be born between 1997 and 2012 are about as heterogeneous as those of any other generation.

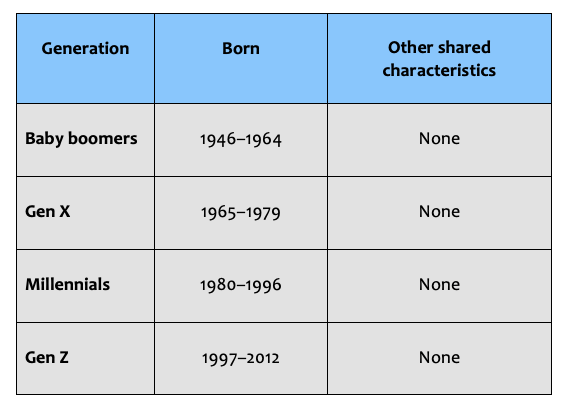

In case you need a handy reference for this point, I have updated my generational guide to include Gen Z.

Psychologically speaking, there is surely as much commonality of individual traits across generations as there is within them. In other words, I think Bernbach’s advice to focus on ‘simple, timeless human truths’ is probably more applicable than, say, ‘memes are the future of marketing’. (You might think that’s a quote I made up for the sake of hyperbole. You’d be wrong.)

Personally, I think we should be a little less obsessed with the zeitgeist and a little more concerned with the leitmotifs of human existence. This is hardly a groundbreaking suggestion, of course, and others have said it much better than me, but it bears repeating because we seem to have developed a collective amnesia about some basic tenets of marketing.

One of the scenes in Chariots of Fire involves Harold Abrahams training to the soundtrack of Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘For he is an Englishman’. It’s a powerful juxtaposition given that Harold didn’t see himself as a typical Englishman at all.

And just as it would be wrong to say that ‘Englishman’ was a sufficient description of Harold Abrahams, it is wrong to suggest that any of us is simply a product of our demographics.

As Eric Liddell says: ‘Everyone runs in their own way.’ As marketers, we would do well to heed that sentiment.