A couple of weeks ago, on the increasingly toxic psychological dumpster-fire that is Twitter, someone shared this timely timeline cleanser. Taken from an interview with Paul Simon, it’s 4 minutes of brilliance that I implore you to watch.

Aside from being a lovely musical demonstration, this video also serves as a superb example of the creative process more broadly (as copywriter Carolyn Barclay expertly summarises in this LinkedIn post).

Personally, I had no idea that Bridge Over Troubled Water drew on all these, shall we say, inspirations. There is certainly nothing inherent in the song that makes them obvious – and nor would you suspect that they come from such varied sources. The finished product sounds seamless and original (or at least it does to my unsophisticated ears).

And that, I think, gets to the heart of the matter – that creativity is often a process of making links between disparate influences to synthesise something new.

Another good example of this is one of my favourite artists: Girl Talk. If you’re not familiar with Girl Talk, all I can say is I feel sorry for you and strongly encourage you to rectify this situation – it will make your life 35% more fun.

Shameless fanboy-ing aside, let me explain why this example is relevant.

Girl Talk (aka Gregg Gillis) is a DJ/producer who specialises in mashups of other artists’ tracks. To give you an idea of just how many sources he uses in his compositions – and how eclectic they are – take a look at this visualisation of his ‘All Day’ album. You can click on the individual bars to see the details of each track.

To me, the really impressive part about this album is that it doesn’t sound like a fragmented hodgepodge – it’s a coherent piece of work that is quite different from its constituent parts. To wit, when I now hear the component songs on their own, I find myself half-expecting a bass drop or an Ice Cube lyric that never comes – because it wasn’t on the original track.

In other words, the work is simultaneously familiar and new.

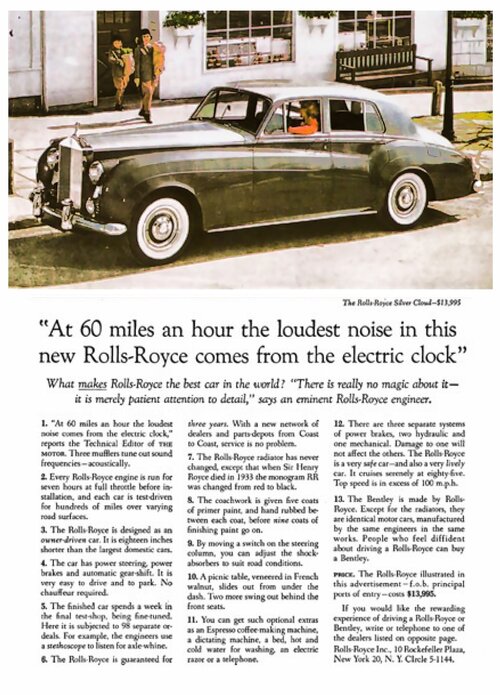

And of course, there are examples of this in advertising too. Such as this famous ad by David Ogilvy.

That headline was lifted, word for word, from an earlier one for the Pierce-Arrow car.

Amateurs imagine original, quirky approaches work best. Not so: what matters is to say the right thing. Something that promises a strong benefit or escape from something people dislike.

And by the way, those previous two paragraphs aren’t mine – I stole them verbatim from this article by Drayton Bird.

As Drayton alludes to here, our industry’s obsession with originality is myopic.

If Paul Simon can use a Bach melody, surely we can draw some inspiration from the advertising of the past. Bach lived more than 200 years ago (which roughly equates to a millennium in ad agency years) – yet some people in advertising eschew influences that are even 20 years old, let alone 200.

There are many examples of brilliant work from the earlier days of advertising, of course, so ignoring it due to a misguided pursuit of originality is downright silly.

Imagine if physicists deliberately avoided building on the work of Newton or Einstein, for the sake of being original. Advertising isn’t physics, to state the ridiculously obvious, but the principle is relevant nevertheless.

To use another scientific analogy, creativity is more often a process of inheritance than a de novo event. The magic lies in the transformation of what is inherited – so that what’s old becomes new again (to steal a line from Stephen King).

As Pablo Picasso – who was no Girl Talk, but still a pretty decent artist – famously said: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”